Apraxia

Apraxia

After brain injury it may happen that someone cannot perform everyday actions or movements properly, even though a request or command is understood.

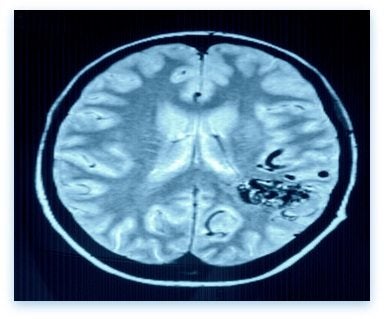

This is not caused by paralysis or awkward coordination. Not even by visual neglect or unwillingness. These tasks were carried out very well before the brain injury happened. The muscles needed to perform the task work properly. Apraxia is an acquired disorder of motor planning. It is caused by damage to specific areas of the cerebrum. Apraxia is most often due to a lesion located in the left hemisphere of the brain, typically in the frontal and parietal lobes.

Many people with apraxia are no longer able to be independent and may have trouble performing everyday tasks.

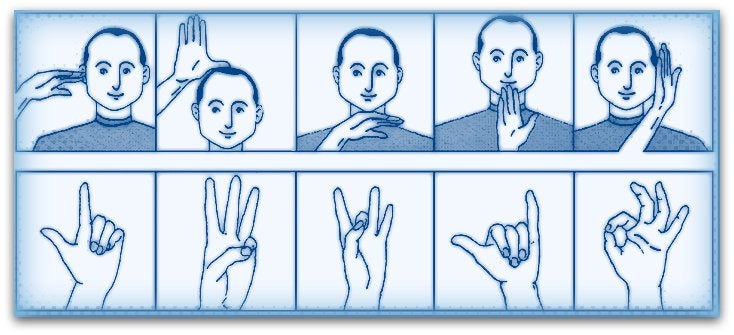

picture above: difficulty copying a gesture

Apraxia may be due to a disturbance in the planning and sequence (ideational apraxia), but also by a disorder in the handling of objects (ideomotore apraxia). In some cases, a person may be able to imitate a complex operation immediately after he has seen it, but cannot perform the same operation at a later time. The ability to copy someones acts may be intact, while commands or spontaneous actions can not be performed.

Another possibility is that someone with apraxia can perform unconscious actions, but cannot consciously perform movements. For example: he may succeed in scribbling on the ear when it is itching, but may fail to imitate this activity.

Going on with an act or or keep repeating the same is called perseveration, which is a form of apraxia. Conversely, the impersistentia motorica, is when someone can not sustain a move. A verbal apraxia exists when the muscles of the mouth can not be controlled to form words correctly. The muscles still work well.

Dyspraxia

A milder form of apraxia is called dyspraxia. A reduced ability to coordinate, perform, plan or carry out specific movements even when there is no paralysis. The person may appear as very clumsy.

The most common causes of acquired apraxia are:

- Brain tumor

- Condition that causes gradual worsening of the brain and nervous system (neurodegenerative illness)

- Dementia

- Stroke

- Traumatic brain injury

Different types of apraxia:

- ideational or conceptual apraxia

Washing and dressing, we all learned from an early age to do it in a certain order. In people with ideational apraxia (the disturbed order handling), you see an impaired ability to complete multistep actions for example: someone forgets to put water in the coffeemaker or is putting on shoes before putting on socks. There may be a problem too with a loss of ability to voluntarily perform a task when given the necessary tools or objects, for instance if given a toothbrush, someone might try to comb his hair with it. Sometimes called ideomotore apraxia

- constructional apraxia

In this form of apraxia the spatial aspect of an act is disrupted. For example someone can not properly (re) draw or construct simple figures.

- limb kinetic apraxia

In this apraxia the inability is to make acccurate or precise movements with a finger, an arm or a leg.

- buccofacial or orofacial apraxia

In this form of apraxia, the person may have difficulty carrying out movements of the face on demand; lips, tongue, eyes. For example, an inability to lick one's lips or whistle or blink one's eyes.

- oculomotor apraxia: Difficulty moving the eye, especially with saccade movements that direct the gaze to targets. This is one of the three major components of Balint's syndrome.

- apraxia of speech (AOS): Difficulty planning and coordinating the movements necessary for speech.

Tips:

Maintain a relaxed, calm environment.

Take time to show someone with apraxia how to do a task, and allow enough time for them to do so.

Do not ask them to repeat the task if they are clearly struggling with it and doing so will increase frustration.

Suggest alternative ways to do the same things, for example, try a hook and loop closure instead of laces for shoes.

It can sometimes help the person with apraxia if the act is split in parts or if operations are simplified.

Also concrete commands given during the execution of an action may help. Someone may benefit if everything is laid out in the correct order or if pictures are used or icons in the form of a roadmap.

| Support | Example |

|

Ask questions about the task to start the task

Ask questions about the task itself

Clarify the questions through gestures

Start the activity together

Show pictures of the task

Place objects you will need in order

Point at the objects

Name objects in the correct sequence

Say out loud what needs to be done

Let eachother know how the activity went on |

The moment your partner sits in front of the sink, you ask him if he wants to wash his torso; in this way you help to start.

If your partner doesn't make a move to start, you'll ask: "what do you need?"

Make a washing gesture Open the tap together, put the hand of your partner over the tap or move the hand towards the tap When you are making coffee together, show pictures of making coffee first. Take the coffee, take the coffeefilter

When putting clothes on you can point at them

You can give the clothing

When putting on a bouse you can say: take the blouse, open up the buttons, put your ar in the sleeve etc.

If the different steps of a task went well, tell your partner

|

Resources:Hugo Liepman Heilman and Rothi; model of apraxia, occupational therapy guideline for diagnosis and treatment of apraxia in stroke clients, neuropsychological treatment.nl, brain foundation Netherlands, Slotervaart hospital treatment after a stroke, BTSG library innovation in the elderly, St Lievens Hospital neurology care program OVL , Logopedie.nl, Apraxie.org, Slingeland hospital ergotherape, MT Banich (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. 2nd edition. Houghton Mifflin Cie and J.B.M. Kuks, J. W. Pike, H.J.G.H. Oosterhuis. Clinical Neurology 15th Edition, Bohn Stafleu Of Loghum, Wood, 2003, ISBN 90-313-4028-6 National Aphasia Association, NIH / National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Adams, Principles of neurology textbook of Clinical Neurology 3rd ed. Philadelphia PA Saunders Elsevier 2007, US national Library of Medicine