Cognitive problems

2 Problems with Attention and Concentration

3 The implications of emotions and conduct

4 (Neuro-)Fatigue

INTRODUCTION

The term 'cognition' is derived from the Latin word 'cognoscere', which means to know. Cognition concerns brain functions that are necessary for perception, thinking, remembering knowledge and applying and understanding this knowledge properly.

Brain injury can have a major impact on these functions. We call that cognitive consequences. Congition is central to neuropsychology.

Cognitive consequences can be mapped through a Neuropsychological Examination.

Memory problems, fatigue, anxiety, irritability. These are some examples of cognitive symptoms that patients with brain injury may experience. These consequences sometimes appear only months or years after the brain injury.

1.What is COGNITION?

Cognition is a concept from neuropsychology. Cognition involves the brain functions that are necessary for perceiving, thinking, understanding, remembering knowledge and applying knowledge in the right way.

Cognition is divided in the following three types:

- Basic Cognition includes attention, learning, memory, perception, thought and language.

- Metacognition consists of judgment, reasoning power and realism.

- Social Cognition includes emotion, practical language skills and empathy.

Cognitive problems occur in areas of knowledge, perceiving and understanding. Difficulties with memory, concentration and thinking speed are the most common.

Cognition is measured by an intelligence test. This measures a total IQ (TIQ). TIQ is divided between a verbal part (VIQ), which focuses on verbal skills and knowledge and a performal section (PIQ), which focuses on action-oriented thinking.

By means of the tests for performal IQ it is determined whether a person can deal with problems in a practical manner. Also motor skills and spatial awareness are investigated.

In people with brain injury very large differences between the VIQ and PIQ may have emerged by the injury. This is called a discordant intelligence profile, Verbal - Performal gap or VIQ PIQ discrepancy.

However, a Verbal - Performal gap can also occur in highly intelligent individuals and in people with autistic disorders. So, a VP gap doesn't have to be the result of brain injury since it can also occur in people without brain injury.

More about the VIQ PIQ discrepancy

After a brain injury one or more problems in the cognitive area may arise:

awareness

understanding

intelligence

concentration

orientation in time, place, person and space

representation

self-perception

problem solving skills

decision power

memory

That means:

Attention and concentration deficits

Delays in the processing of information (mental slowness / pace)

Impaired intellectual functioning (sometimes only partial)

Memory problems, impaired learning ability

Orientation Problems person, place, time and space

Visual-spatial problems

Problems with coordinating daily and / or complex actions (apraxia)

Problems recognizing things, perceiving

Language problems

Problems with the arithmetic

Problems with executive functions

2.PROBLEMS WITH ATTENTION

AND CONCENTRATION

- Focusing the attention on something (a conversation, an activity, an exercise).

- Retaining the attention to the activity.

- The distribution of the attention. If this is difficult, it is almost impossible to perform simultaneously two or more tastks. For example: talking whilst doing the dishes or making coffee and having a conversation becomes impossible. But also following a conversation with multiple people is difficult.

2.2 NEGLECT

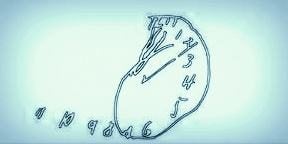

Neglect is a disorder that occurs mainly in a damage in the right hemisphere (with the failure symptoms left). There is no "attention" perception of the affected (usually left) side: people "ignore" the affected side and the space around it: This side is not seen, not felt or seen.

Neglect can involve all kinds of problems in daily life:

- If someone is sitting on a chair or lying in bed, the crippled arm can still hang down. Injuries can easily arise that are also less noticed by the neglect.

- People often run into things on the affected side (to obstacles, door frame), because that side is not observed.

- 'Ignoring' people on the wrong side often happens. Not out of unwillingness, but because they are not observed.

- When eating, half of the plate is left uneaten, is 'forgotten' to eat.

- Only one half of the face is shaved.

- Only one side of the face is done with make up.

- Car driving, cycling or taking part of traffic is very dangerous because on the affected side objects are not detected.

- Doors are walked by on the side of neglect, and so someone can get lost.

- In extreme cases, the patient doesn't recognizes his own cripple arm and leg as his own limbs. He feels a strange leg lying in bed.

Drawing of a clock, as seen by a patient with neglect

2.3 MENTAL INERTIA

Many people with brain injury complain that thinking is slower and takes a lot more time and attention. If everything is slower in the head, the outside world seems an accelerated played movie.

It also takes a lot of energy to follow all that. If a lot is said or done at the same time, someone can not take the pace anymore. Mental pursuits such as reading a book or transferring money via the internet, takes a lot of time and can be exhausting. The world is going too fast ...

A slower pace in the processing of information is noticeable when the patient responds to a question or command, remarkably with a long time. By that slowed pace, people with brain injuries are more sensitive to time constraints, and they may feel they are running out of time.

Slowed information processing can have a negative influence on other attentional functions (eg when dividing attention), on memory (eg storing information), or the organization and planning of behavior.

2.4 MEMORY PROBLEMS

Remembering new information takes more time than before and the information is often not retained properly.

This also has to do with attention problems and mental sluggishness. Additionally, digging up information from memory is difficult.

Furthermore, it happens that people with brain damage do not recognize certain objects or can not remember certain faces.

It is now known that practicing with various memory games hardly changes anything in daily life.

By the lack of the ability to generalise (the transfer of training effects in the practice situation to everyday life), the training must always be focused on what one wants to learn.

Forgetting messages, loss of keys, forgetting appointments, and so on, therefore can not be solved by card games and computer training.

So memory training do not have the effect that it improves memory. It is not the case that you're automatically going to remember better after a memory training. You learn to remember better through all sorts of memory tricks (strategy training, training compensation).

Most memory training include the following: more attention, more time, more repetition, learn to make more connections, learn to think more in pictures (visual support) and organize better and more!

Attention

Time

Repetition

Associate or Link (connections)

Visualize (make link images in your memory)

Organize

A good site about memory training is by neuropsychologist Feri Kovács. Click here:

2.5 PROBLEMS WITH ACTING; apraxia

Apraxia is a cognitive disorder by which people can not perform operations properly.

For example, a fork is used for eating soup. A toothbrush is used for combing the hair.

Or operations are reversed; when dressing, the pants are put on first and the underpants over it.

Often acts which consist of several steps are the hardest. Examples include making coffee or make a phonecall.

2.6 PROBLEMS WITH ORIENTATION

This means that someone does not knows well what date or time it is, or where he is exactly. The spatial orientation is worse: someone does not know the way home.

2.7 PROBLEMS WITH PLANNING AND ORGANIZING

If someone wants to do something, he has to plan. It is not only for difficult tasks only as do the shopping, but also for a simple activity like making phone calls. The ability to plan and organize is often gone after brain injury.

Performing a task might succeed, but than it should be clear what to do exactly. "Are you cooking dinner tonight?" Is much too complex.

'Making dinner' concerns a several sub-tasks: invent a menu, looking for a good recipe, making a shopping list, going to the store, handling money, cooking dinner, several pots and pans, and ensure this all is ready at a certain time.

2.8 NO UNDERSTANDING of LIMITATIONS

Especially people with brain injuries on the right side of their brain (with failure symptoms on the left side of their body) do have a remarkably poor understanding of their capabilities and limitations.

Someone knows that he has had a stroke, but does not experience the limitations as the environment does. This brings difficulties with the rehabilitation: if someone does not know what is wrong with him, he can not work on it or train it.

For example, some people do not realize that walking is no longer possible without a cane, and then fall. Or someone does not see that driving is dangerous.

2.9 PROBLEMS with UNDERSTANDING spoken and written LANGUAGE

Aphasia is the term for a language disorder. In people with aphasia, the use of the language is disturbed. Speaking, reading and writing may be limited. The concept of what another person says may be impaired.

How the language faculty is affected varies per person. Some people with aphasia can not speak. Others talk incessantly, but are incomprehensible. Still others are only unable to think of the right word.

More subtle is the language disorder in which people no longer understand figurative speech and take everything literally, even sayings.

3. EFFECTS on the AREA of EMOTIONS and CONDUCT

Not only cognitive skills can be affected by brain injury. There are often problems with emotions and behavior. To deal with it is not only difficult for the patient, but also for the environment. Your brain is you! ...

3.1 DEPRESSION

Depression is a condition that belongs to the 'mood disorders'.

A depressive mood occurs when there is abnormal sadness and/or lethargy for a longer period of time. This depressed mood lasts for more than two weeks.

The sadness or lethargy is often accompanied by loss of interest, zest for life or pleasure. In addition, the following complaints may occur: sleep disorders, fatigue, concentration problems, weight changes and/or thoughts about death.

Sadness (depressive complaints) is actually one

normal emotion after the occurrence of acquired brain damage and is consistent with an acceptance problem.

Depression due to loss of health

Life with brain injury can be completely different. This is often difficult to accept. A person may henceforth need a wheelchair, cannot go home or cannot do his or her job.

If a person can no longer express her- or himself due to aphasia, this can play an important role. That can be very frustrating.

Apraxia can be just as frustrating. For example, you no longer know how to get dressed and you put on your underpants over your long pants and you realize that it is not right, but what is the right way?

These experiences of loss can lead to a lot of grief, which is similar to mourning. A person may become depressed.

Depression is accompanied by much psychological suffering. But it may also deteriorate physical functioning.

This is called living loss: someone is still alive, but there is mourning for what has been lost. The person may become depressed.

Depression causes a lot of psychological suffering. But physical functioning also deteriorates. In fact, becoming depressed is a healthy reaction to an intense and traumatic event. That's how it goes with a process of dealing with it.

Depression due to the location of injury in the brain and neurobiological factors

Depression may occur as a direct result of the location of the injury in the brain.

People with left hemisphere injuries appear to be slightly more likely to develop a depression. Although that may differ for people who are left-handed.

There are studies that refute this 'lesion location theory'. There may also be blood vessel-related causes (vascular causes) and neurobiological factors that may play a role; the 'cerebral immune activation and inflammation factor' (cytokine hypothesis).

Depression occurs in 20-50% of people with a stroke in the first year. Depression is therefore the most common

'neuropsychiatric syndrome' after a stroke.

This is called post-stroke depression (PSD).

In 25% of people with traumatic brain injury, this also occurs in the first year. No figures are yet available for other causes of brain damage.

However, it is necessary to distinguish between depression and depressive features. People with brain damage often score high on a short 'test for depression' because they are tired and take less initiative, suffer from loss of concentration or have a changed sleep pattern. These could be pure consequences of the brain injury, but do not say anything about the mood. Caution: neurofatigue is different from just being tired.

Depression due to overload

Being under pressure due to overexertion is common in people with brain damage. Many people with brain damage have a limited capacity to cope and therefore end up in burnout more often. Maybe they still want to, but they simply can't perform anymore. It is important to match someone's load capacity with what is required.

See our page on this subject here.

3.2 Easily overwhelmed by emotions, Easily overstimulated

A common complaint is that people get overstimulated much easier. It is like a healthy person, who not only has to multitask in fifteen tasks, but in doing so, also must drive a car in thick fog with 180 miles an hour, while he must analyze a piece of music for his job, counting the half notes and counterfeit notes, and counting how many quarters notes are inside.

That's impossible .. a person may react agitated. The situation that the kids on the backseat ask a question to you about the year that Charlemagne died ..., while you are driving the car, it will be comparable to the situation of someone with brain injury ... This person is not able to do all the tasks that are demanded and can be easily tempered.

Tears may just flow at the slightest emotion, without feeling the need of crying, which itself often is perceived as a nuisance. Read more about overstimulation.

3.3 DIFFICULTIES IN MANAGING IMPULSES

People may find it difficult to control their impulses. The brake is off. For example, someone swears faster if something fails. He might become unrestrained in eating and snacking, or being uninhibited in sex.

3.4 SHOWING LITTLE INITIATIVE / APATHY

It may happen after an incident that caused brain injury, that the brain injured person shows a lack of initiative. There appears to be reduced activity and lack of involvement.

The person may appear listless, indifferent, lack emotion and be difficult to motivate. There doesn't seem to be any connection between the severity of the injury and apathy or how long the brain injury has existed and the apathy.

Apathy is described as 'a persistent decrease in motivation, responsiveness and goal-directed behavior'. It meets specific diagnostic criteria by which it can be distinguished from a depression.

It is often difficult for the environment if someone takes no more initiative and does not show interest.

Sometimes this is the result of depression, but it can also be the result of the brain damage itself. It mainly occurs in people with a stroke in the frontal lobe. People can also be emotionally very flat.

Apathy is a syndrome of primary loss of motivation, which is not attributable to reduced consciousness, cognitive impairment or emotional problems.

Apathy can manifest itself in, among other things, the lack of goal-oriented behavior, decrease in goal-oriented thinking and emotional indifference with a flat affect (feeling).

In whom and how often does apathy occur?

Apathy is seen in neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease (63-90%), Frontotemporal dementia/FTD (92%), vascular

dementia /VD (72%), Lewy Body dementia (57%), in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy/PSP, in CADASIL, in Parkinson's disease, Huntington.

It also occurs in brain injuries such as a stroke CVA (36%), traumatic brain injury (20-70% with an average of 49%), infections in the brain and brain tumors.

Furthermore, apathy occurs in several mental disorders (including depression, PTSD, and schizophrenia).

Apathy is a warning sign of dehydration, exhaustion, liver failure, fors, poisoning and substance use (for example cannabis or alcohol), shock, underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) and other conditions.

Rule out illness, depression, side effects of medication

Apathy can be caused by the brain damage itself as a direct consequence. However, sometimes apathy is a symptom of another condition or of a depression as we wrote in the paragraph above. It is therefore important to rule out a clinical picture or possible depression. When depression is diagnosed, the depression must be treated first. It is also important to distinguish apathy as side effects of medicines.

We recommend that you discuss this with the doctor.

Recognize, acknowledge and treat where possible

Apathy after brain injury can be an obstacle on the road to rehabilitation and recovery.

That is why it is important to recognize, acknowledge and treat apathy where possible.

Where in the brain?

Apathy has been linked to damage to multiple brain regions, including the frontal lobe, basal ganglia, and cingulate gyrus. A blockade of dopamine pathways also appears to play a role.

How to approach someone?

It is important to treat someone who exhibits apathetic behavior clearly and repeatedly with 'gentle pressure'.

A fixed structure and encourage learning automatisms is recommended.

The goal is for the person to perform as many routine tasks as possible, such as washing and dressing him-or herself and other personal care tasks (if possible).

There are certain drugs that may have possible beneficial effects in reducing apathy. The effect is not always clearly proven.

Setting very specific goals can also help. Continue to offer plenty of water, tea or other drinks, so that the person does not become apathetic due to a lack of fluid.

Caregivers

It is often difficult for the environment when a person no longer takes any initiative and seems to have no desire or interest in anything. It is therefore important for the partner or caregiver to monitor his or her own load tolerance and health and to seek help if necessary.

3.5 LIMITED FLEXIBILITY

After a stroke, people often can not cope with changes very well. If something is not going as expected, they can become quite upset. For example, unexpected visit or a setback are hard to process.

3.6 DEPENDENT BEHAVIOR

Some people are showing more and more dependent behavior to their partner or other relatives. They leaves it to them to do the conversations, to arrange things and doing physical activities. The partner will gradually take over responsibilities increasingly, so the behavior gets worse.

4 FATIGUE AND NEUROFATIGUE

The most common complaint after brain injury is a (severe) fatigue and increased need for sleep. Often it is even the main complaint that people have.

The fatigue is so severe that people are limited in their daily activities and social contacts.

Often the fatigue is a combination of physical and mental fatigue. If the brain's sleep center is also affected, the fatigue is twice as large. Read more

Read more....Cognitive Problems: A Caregiver's Guide.

Read more.... Up to 75% of people with cancer experience cognitive problems

Read more... Cognitive Changes : National Multiple Sclerosis Society

Read more ...Cognitive problems | Stroke Association

Read more.... Cognitive Problems After Traumatic Brain Injury

Read more.... Cognitive problems in MS | Multiple Sclerosis Society UK

Resources

Grondslagen van de neuropsychologie Luria, Aandachtsstoornissen. Een neuropsychologisch handboek Eling& Brouwer,

Omgaan met hersenletsel Palm, hersenletsel-uitleg.nl, Attention, mental speed and executivecontrol after closed head injury, Spikman hersenstichting.nl,

Cognitive psychology Neisser,New York,M.T. Banich (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. 2e editie. Houghton Mifflin Cie

J.B.M. Kuks, J.W.Snoek, H.J.G.H. Oosterhuis. Klinische Neurologie 15e druk, Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum, Houten, 2003, ISBN 90-313-4028-6

Caeiro L, Ferro JM, Costa J. Apathy secondary to stroke: a systemic review and meta-analysis.Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;35:23-39.Carson, A. J., MacHale, S., Allen, K., Lawrie, S.

M., Dennis, M., House, A., & Sharpe, M. (2000).Depression after stroke and lesion location: a systematic review. The Lancet, 356 (9224), 122 – 126.

Chase T. Apathy in neuropsychiatric disease: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment. Neurotox Res 2011; 19: 266-278.

Ciurli P, Formisano R, Bivona U, Cantagallo A, Angelelli P. Neuropsychiatric disorders in persons with severe traumatic brain injury: Prevalence, phenomenology, and relationship with demographic, clinical,and functional features.

J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26:116-126. Jorge RE, Starkstein SE, Robinson RG. Apathy following stroke. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(6):350-4.

Lane-Brown AT, Tate RL. Apathy after acquired brain impairment: a systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions. Neuropsychol. 2009;19(4):481-516.

Mikami K, Jorge RE, Moser DJ, et al. Prevention of poststroke apathy using escitalopram or problem-solving therapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(9):855-62.

Marin, R. S. (1991). Apathy: A Neuropsychiatric Syndrome. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 3, 243-254.

R.S.Marin et al. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale Psychiatry Res (1991)

Marin, R. S., Biedrzycki, R. C., & Firinciogullari, S. (1991). Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES, AES-C, AES-I, AES-S)[Database record]. APA PsycTests.

https://doi.org/10.1037/t28570-000

A. T. Lane-Brown & R. L. Tate (2009) Apathy after acquired brain impairment: A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions,

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 19:4, 481-516, DOI: 10.1080/09602010902949207 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1627483013000020

Worthington A, Wood RLL. Apathy following traumatic brain injury: a review. Neuropsychologia . (2018) 118:40–7.

Cranenburgh, B. van (2002). Het belang van inzicht in het geheugen voor de revalidatie. Neuropraxis, 4(1):162-163.C