Frontal lobes

Foreword

The brain works together as a single entity. Brain functions are distributed throughout the brain regions and arise from communication between them. However, certain complaints can be identified within a brain region.

At the front of each cerebral hemisphere are the frontal lobes, the largest lobes of the brain.

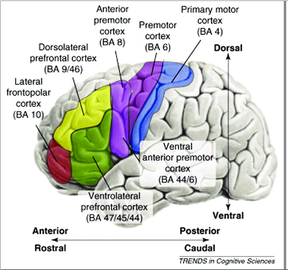

The frontal lobe is divided into, from front to back:

- The prefrontal cortex. The function of this cortex is described further down this page.

- The motor cortex (movement cortex):

- The premotor cortex. Responsible for progeamming movements. See no. 6 on image below (Brodmann area 6).

- The primary motor cortex. Responsible for executing movements. See no. 4 on image below (Brodmann area 4, sometimes also called M1).

Forehead Back of head

The frontal gaze center, which controls eye movements, is located just above the premotor cortex (Brodmann area 8 in the image above).

MRI studies show that damage to the frontal lobe is the most common lesion in mild to moderate traumatic brain injury.

The frontal lobes are the largest lobes of the brain and they are extremely vulnerable to injury due to the fact that they are located at the front of the cranium and because of being near rough boney ridges, (proximity to the sphenoid wing) and their large size.

Causes of head trauma

Common causes include:

- A hit against the dashboard of a car

- A blow or fall on the handlebars of a bicycle

- A hard landing on the asphalt in a motorcycle or moped accident

- A blow from a blunt object

- A collision with a hard object, for example, while playing sports.

Cerebral hemorrhage or stroke

Large blood vessels, both arteries and veins, run through the frontal lobe.

When a bleeding occurs in such a blood vessel, it is called a cerebral hemorrhage. When a blood vessel becomes blocked by a blood clot, it is called a cerebral infarction.

Consequences of damage

The consequences of complaints may vary depending on whether the injury occured on the left or on the right side of the forehead or on both sides. The extent of the injury and the number of interrupted nerve connections also play a role. Last but not least, it is important to know whether the person has compensation options.

It's important to know which functions the frontal lobe is involved in to understand the impact of frontal lobe damage.

The frontal lobe is involved in:

- Planning and executing movements

- Planning, organizing, and structuring

- Memory, working memory

- Concentration

- Impulse control

- Problem solving

- Selective attention

- Decision-making

- Controlling behavior and emotions; the frontal cortex inhibits,

- among other things, deep emotions in the amygdala.

These are the so-called executive functions.

The left frontal lobe also plays a role in speech and language in right-handed people, and conversely, the right lobe in left-handed people.

Lessions in these lobes can lead to problems with emotions, language, impulse control, memory, social and sexual behavior, and reduced empathy. Symptoms can vary from person to person, including their severity, and be experienced differently by the individual. One person with damage in this brain area may experience one or two of the listed symptoms, while another may experience several, or to varying degrees. See also the page on executive dysfunction.

Frontal lobe injuries, regardless of their cause, are characterized by the frontal lobe syndrome.

This syndrome describes a dramatic change in social behavior and the inability to regulate emotions.

A person's personality can undergo significant changes after a frontal lobe injury, especially when both lobes, the left and right, are involved.

We describe the specific characteristics on the special

frontal lobe syndrome page.

More specifically:

- Loss of a simple movement of various body parts (motor function)

- Inability to plan the sequence of complex movements/actions required for complex tasks, such as making coffee

- Loss of spontaneity in interactions with others

- Loss of flexibility in thinking. Loss of initiative

- Perseveration - the inability to stop a single thought

- Inability to concentrate on a task/attention, worsened by stressful circumstances or distractions. The neurons in the frontal lobe then react franticly.

- Mood swings (emotional fluctuations).

- Changes in social behavior and/or personality. For example, lack of initiative, disinhibition or impulsive behavior, reduced ability to assess danger, reduced empathy, lack of understanding of others' emotions. Changes in behavioral regulation.

- Uninhibited anger. Self-awareness that may be lacking. Disinhibition in multiple areas. See the page on uninhibited behavior. Frontal syndrome in frontal lobe damage; dramatic changes in behavior.

- Difficulty solving problems.

- Inability to express language (Broca's aphasia).

The frontal lobes are considered to be the seat of emotional control and personality. There is no other part of the brain where brain damage causes such a wide variety of symptoms.

Movement problems may lead to reduced strength in the arms, hands, and fingers, and difficulty with fine movements.

People with damage to the frontal lobe sometimes show fewer facial expressions. This demonstrates the importance of the frontal lobe for facial expressions. Damage to this part of the brain can also lead to speech problems, such as Broca's aphasia.

Damage to the frontal lobe can affect how flexible you are able to think (divergent thinking) and solve problems. It may also make it harder to concentrate and remember things, even if you recover well from a brain injury.

Researchers have found that people with damage to the left frontal lobe use fewer words, while damage to the right side can lead to excessive talking.

A common characteristic of frontal lobe damage is difficulty responding to the environment. For example, people may persist in certain behaviors (persevering, or continuing without stopping), misjudge risks, fail to follow rules, or have difficulty learning new things.

The frontal lobes also help us orient ourselves in space, including estimating where our body is in relation to other things.

More information about the impact of damage to the frontal lobes you can find on the website of the Centre for Neuroskills.

The prefrontal cortex (dorsal, ventral and orbitofrontal)

The front of the frontal lobe, the prefrontal cortex, is divided into three layers. Each layer has a lateral portion and a medial portion.

- Dorsal part (located at the top)

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- Ventral part (in the middle)

- Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex

- Ventromedial prefrontal cortex

- Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex

- Orbitofrontal part (just above the eyes)

- Lateral orbitofrontal cortex

- Middle orbitofrontal cortex

- Lateral orbitofrontal cortex

The prefrontal cortex is important for working memory.

The brain cells in this part of the brain store information for a short period of time. You can compare it to a notepad or a computer. Information can be stored, erased, and replaced with new information as needed.

Research has shown that stress can significantly disrupt working memory. If you experience unexpected stress, the information in your working memory can even disappear completely. Working memory, which is part of your short-term memory, doesn't function properly under stress or when you're distracted.

Damage to the upper and outer parts of the prefrontal cortex

of the brain (dorsolateral injury) can cause problems with mood regulation.

More specifically, the symptoms per area are illustrated

Consequences of damage in the middle of the frontal lobe

- Dependence on loved ones

- Loss of initiative

- Loss of willpower

- Emotional flatness

- Apathetic behavior

- Paralysis on the opposite side of the body from the brain damage.

- Damage to the right side of the brain causes deficits on the left side of the body, and vice versa

Consequences of damage in the orbital area of the frontal lobe

- Disinhibited or uncontrolled behavior

- Impulsiveness

- Difficulty with self-correction

- Reduced sense of appropriateness and inappropriateness

- Little to no attention to others

- Inappropriate jokes or tactlessness

- Disturbed sense of smell

- Altered sexual behavior

- Frontal syndrome

Testing the consequences of frontal damage

A neuropsychological examination can accurately map damage to the frontal brain areas. During this examination, various tests are administered to measure motor and language skills, as well as tests aimed at assessing social cognition.

Brain damage is not always immediately visible on imaging techniques, as in the image below. Even if an MRI or CT scan shows no abnormalities, a brain injury may still be present. For more information, see our dedicated page.

Resources

Akert, J. M., & Warren, K. (1964). The Frontal Granular Cortex and Behavior (Herz. ed.). New York, V.x.: MC Graw Hill. Barncard

Benson, D. F., & Blumer, D. (1975). Psychiatric aspects of neurological disease. New-York, V.S.: Grune & Stratton.

Brookhart, J. M., Mountcastle, V. B., & Brooks, V. B. (1981). The nervous system: Motor control. Maryland, V.S.: American Physiological Society,.

Brown, J. W. (1972). Appraxia, and agnosia;: Clinical and theoretical aspects,. Springfield, Illinois: C.C. Thomas.

DBCLS | Database Center for Life Science [Foto]. (z.d.-a). Consulted from https://dbcls.rois.ac.jp/index-en.html

Devilbiss, David M, Jenison, Rick L. ., Berridge, Craig W. , Stress-Induced Impairment of a Working Memory Task: Role of Spiking Rate and Spiking History Predicted Discharge” in PLoS Computational Biology published 13 Sep 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002681 Stress Breaks Loops that Hold Short-Term Memory Together | Neuroscience News http://t.co/AG9873mS

Drewe, E. (1975). Go - No Go Learning After Frontal Lobe Lesions in Humans. Cortex, 11(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0010- 9452(75)80015-3

Eyskens, E., Feenstra, L., Meinders, A. E., Vandenbroucke, J. P., & Van Weel, C. (1997). Codex Medicus (10e ed.). Maarssen, Nederland: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.

Hersenletsel uitleg | Hersenletsel-uitleg.nl. (z.d.). Geraadpleegd van https://www.hersenletsel-uitleg.nl/

https://www.hersenletsel-uitleg.nl/gevolgen-per-hersengebied/frontaal-kwab-voorhoofdskwab

Kolb, B., & Milner, B. (1981). Performance of complex arm and facial movements after focal brain lesions. Neuropsychologia, 19(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(81)90016-6

Kuks, J. B. M., Snoek, J. W., Oosterhuis, H. G. J. H., & Fock, J. M. (2003). Klinische neurologie (15e ed.). Houten, Nederland: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Kuypers, H. G. J. M. (2011). Anatomy of the Descending Pathways. Comprehensive Physiology, . https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.cp010213

Leonard, G., Jones, L., & Milner, B. (1988). Residual impairment in handgrip strength after unilateral frontal-lobe lesions. Neuropsychologia, 26(4), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(88)90112-1

Levin, H. S., Amparo, E., Eisenberg, H. M., Williams, D. H., High, W. M., McArdle, C. B., & Weiner, R. L. (1987). Magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography in relation to the neurobehavioral sequelae of mild and moderate head injuries. Journal of Neurosurgery, , 706–713. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1987.66.5.0706

Miller, L., & Milner, B. (1985). Cognitive risk-taking after frontal or temporal lobectomy—II. The synthesis of phonemic and semantic information. Neuropsychologia, 23(3), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3932(85)90023-5

Milner, B. (1982). Some Cognitive Effects of Frontal-Lobe Lesions in Man. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 298(1089), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1982.0083

Pictures from:

Polygon data are from BodyParts3D maintained by Database Center for Life Science(DBCLS).

Picture Brodman area: Door Henry Vandyke Carter - Henry Gray (1918) Anatomy of the Human Body (See "Boek" section below)Bartleby.com: Gray's Anatomy, Plaat 726, Publiek domein, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=620390

Semmes, J., Weinstein, S., Ghent, G., Meyer, J. S., & Teuber, H. (1963). Impaired orientation in personal and extrapersonal space. Brain, 86(4), 747–772. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/86.4.747

Stuss, D. T., Ely, P., Hugenholtz, H., Richard, M. T., LaRochelle, S., Poirier, C. A., & Bell, I. (1985). Subtle neuropsychological deficits in patients with good recovery after closed head injury. Neurosurgery, 17(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006123-198507000-00007

Walker, A. E., & Blumer, D. (1975). The Localization of Sex in the Brain. Cerebral Localization, , 184–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642- 66204-1_15