Aggression

Behavioural changes such as agitation and aggression occur in approximately 10 to 35% of people with non-congenital

brain damage, both in the acute and chronic phases. This can be a temporary phase or, in some cases, long-lasting.

In the first six months after brain injury, approximately one third of people with brain injury exhibit aggressive behaviour. That number drops to about a fifth of people after five years. Aggression in the first three months is nevertheless a reasonable indication of aggressive behaviour after years.

Verbal aggression is most common. Aggression and impulsiveness often occur together.

In the professional literature, the term 'aggression' is used to refer to symptoms of disinhibition, anger and irritability as a result of not being able to control behaviour and emotional impulses.

Aggressive behaviour after brain injury is often a direct result of damage to brain areas responsible for brain damage emotion and behaviour.

Neurobiological causes also play a role. Furthermore, if a person showed rebellious, agitated or aggressive behaviour or had a psychiatric condition before the brain injury, the aggression after the injury is not only due to damaged brain areas. Brain injury can also be accompanied by PTSD (post traumatic stress syndrome) that can have a major influence on behaviour.

Damage to specific brain areas

The question is whether a person with brain damage is consciously and intentionally aggressive.

On the one hand, anger may indicate impaired cognitive control, such as emotion regulation.

But the brain's reward system also plays a special role in anger and a response to frustration.

Aggressive behaviour after brain injury is often a direct result of damage to brain areas and the neural circuits between the brain areas responsible for regulation of emotion and behaviour, such as

the frontal lobe (prefrontal cortex [PFC]).

That lobe plays an important role in problem solving, reasoning, and impulse control. For example, the frontal lobe inhibits the amygdala, one of the most important emotion centers of the brain.

Damage to the frontal lobe (prefrontal cortex) reduces this inhibition of the amygdala, which can result in higher levels of aggression.

All of these frontal lobe functions are all necessary to regulate a person's behaviour. When the frontal lobe becomes damaged, it can affect behavioural skills. This can lead to aggressive behaviour. There is great difficulty in controlling inappropriate behaviour. This is often seen in combination with risky behaviour and poor decision-making after brain damage. The other brain areas involved in aggressive behaviour can be found in the drop-down menu.

Causes

Although aggressive behavior may seem unpredictable, it is often caused by emotional or physical discomfort.

The frustrations of the changes caused by the brain injury can put so much pressure on a person that it can cause an 'explosion'.

A person may feel so unworthy, dependent and no longer in control of life. By this he or she may be more likely to take something as an insult or reproach that this can be enough for an aggressive outburst.

Prevention is better than ...

Anyone who can recognize and prevent most triggers will go a long way in helping you learn to control aggression.

Relatively simple environmental changes can often lead to a major reduction in problem behavior.

A low-stimulus environment, a fixed daily structure and a consistent, directive approach are of great importance.

We sympathize with all parties. That is, we sympathize with people with brain injury and with people who are confronted with aggression from someone with brain injury.

Coping strategies for the person with aggression due to brain injury

- Take a Time-out. Get away from the situation that made you so angry.

- Ask yourself what caused the aggressive outburst. Were you in pain? Were you very tired? Did everything take a lot of effort? Did you search for words? Couldn't you express yourself? Did you feel ashamed of who you are? Did you feel helpless? powerless, disappointed? Did you feel like you were a burden to those around you? Were you afraid? Were you hungry and did you have low blood sugar? Was there too much noise, too much bustle or too much bright light? Did you have to do too much? too much was expected of you? Did everything happen too fast? Is the recovery too slow or do you see that there is no recovery? Did you feel a sense of grief? Did you use alcohol or some form of drugs? If so, do you understand that your emotions are even less inhibited by alcohol and drugs? That this can lead to dangerous situations?

- Always apologize when you have calmed down. People can't see into your head what happened. You can try to explain this later at a quiet moment. Realize that others may be very shocked.

- Share how you felt and what caused it.

- Understanding is always essential.

- A large part of emotional outbursts is a result of damage in specific brain areas. With this knowledge into why it works this way, you can ask for help from a professional.

- Find out how you can find a better balance between load tolerance and effort. Realize that people with brain injuries can get tired very quickly. It has been scientifically proven that a brain with injuries tire more quickly (neurofatigue).

- If your anger stems from pain and physical discomfort, ask a doctor, physiotherapist or occupational therapist to look at your situation. Look for help, for example here or here.

- Try to think together about ways for future anger to be expressed differently. Depending on the cause (emotional or physical discomfort), a punching bag may be used or pulling on a towel or hitting with a towel.

- Don't be ashamed to seek help with aggression. There are different ways to learn to deal with it. A good care provider who understands brain injuries can teach you these ways. For example, a behavioral therapist, neuropsychologist, behavioral neurologist, etc.

- Medicines may provide some relief.

For bystanders who are confronted with aggressive behavior

- Safety: Always ensure the safety of children, adults and pets.

- Withdraw: Take a time-out and avoid the argumentative person for a while.

- Always explain (as calmly as possible) why you are leaving for a while and taking a time-out.

- Make sure you have your own space to go to for a while. Your space.

- When peace is restored, try to find out together with the person who had such an aggressive discharge, what caused it. Make it negotiable.

- Strategy: Try to think together about ways to express future anger differently.

- Help: Ask for help from a behavioral therapist, neuropsychologist, behavioral neurologist, relationship counselor specifically for brain injuries, etc. Find someone who has knowledge of brain injuries. Unfortunately, not everything can be learned.

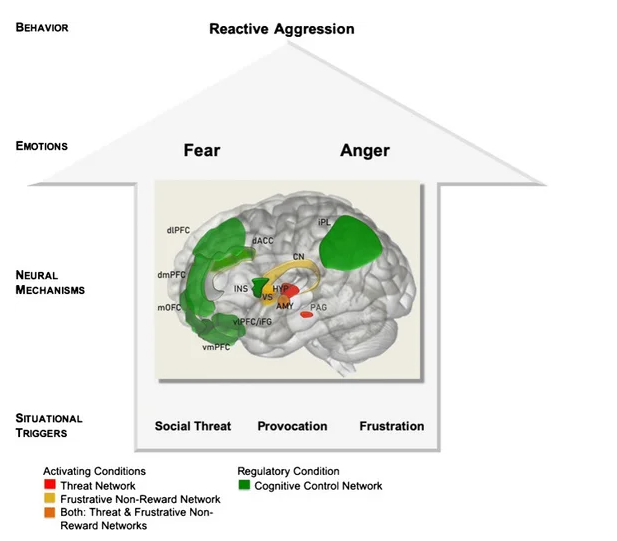

Brein areas that are sensitive to threat

Image from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7661405/figure/Fig1/

Most important brain areas with threat sensitivity and reward sensitivity as a prerequisite for reactive aggression:

Amygdala: almond-shaped areas

Caudatus nucleus /Nucleus caudatus: tail nucleus, part of the basal nuclei

Hypothalamus: part of the limbic system

dACC: dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, girdle coil, just in front of the back

dlPFC: dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex = Cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe at the posterior side

dmPFC: dorsomedial pre-frontal cortex = Cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe at the posterior-middle side

IFG: inferior frontal gyrus Gyrus = inferior gyrus, the brain folds in the forehead

Insula = island of Reil

IPL: inferior parietal lobes

Medial orbito frontal cortex: Cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe near the center of the eye sockets

Peri-aqueductal gray

Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex = Cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe on the ventral side

Ventromedial prefrontal cortex = Cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe on the ventral side

Ventral striatum (the striated body on the ventral side) Part of the basal nuclei.

Resources

Abdolalizadeh A, Moradi K, Dabbagh Ohadi MA, Mirfazeli FS, Rajimehr R. Larger left hippocampal presubiculum is associated with lower risk of antisocial behavior inhealthy adults with childhood conduct history. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 15;13(1):6148. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33198-9. PMID: 37061611; PMCID: PMC10105780.

Arciniegas DB, Wortzel HS: Emotional and behavioral dyscontrol after traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2014; 37:31–53

Bekiesinska-Figatowska M, Mierzewska H, Jurkiewicz E. Basal ganglia lesions in children and adults. Eur J Radiol. 2013 May;82(5):837-49. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.006. Epub 2013 Jan 10. PMID: 23313708.

Bertsch K, Florange J, Herpertz SC. Understanding Brain Mechanisms of Reactive Aggression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020 Nov 12;22(12):81. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01208-6. PMID: 33180230; PMCID: PMC7661405.

Brain injury and aggression, ca we get some help https://n.neurology.org/content/76/12/1032

Dyer KF, Bell R, McCann J, et al.: Aggression after traumatic brain injury: analyzing socially desirable responses and the nature of aggressive traits. Brain Inj 2006;20:1163–1173

Durga Roy , M.D., Sandeep Vaishnavi, M.D., Ph.D., Dingfen Han, Ph.D., Vani Rao , M.D. (2017 may) Correlates and Prevalence of Aggression at Six Months and One YearAfter First-Time Traumatic Brain Injury. https://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16050088

Falkner AL, Wei D, Song A, Watsek LW, Chen I, Chen P, Feng JE, Lin D. Hierarchical Representations of Aggression in a Hypothalamic-Midbrain Circuit. Neuron. 2020

May 20;106(4):637-648.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.02.014. Epub 2020 Mar 11. PMID: 32164875; PMCID: PMC7571490.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al.: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV–Clinical Version (SCID-CV) (User’s Guide and Interview). Washington, DC, AmericanPsychiatric Publishing, 1997

Hersenletsel-uitleg

Rapoport M, McCauley S, Levin H, et al.: The role of injury severity in neurobehavioral outcome 3 months after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychiatry NeuropsycholBehav Neurol 2002; 15:123–132 Medline,

Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr. 2015 Jun;20(3):254-79. doi: 10.1017/S109285291500019X. Epub 2015 May 4. PMID:25936249. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25936249/

Sabaz M, Simpson GK, Walker AJ, et al.: Prevalence, comorbidities, and correlates of challenging behavior among community-dwelling adults with severe traumaticbrain injury: a multicenter study. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2014; 29:E19–E30

Silver JM, Yudofsky SC: The Overt Aggression Scale: overview and guiding principles. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1991; 3:S22–S29

Zhu Z, Ma Q, Miao L, Yang H, Pan L, Li K, Zeng LH, Zhang X, Wu J, Hao S, Lin S, Ma X, Mai W, Feng X, Hao Y, Sun L, Duan S, Yu YQ. A substantia innominata-midbraincircuit controls a general aggressive response. Neuron. 2021 May 5;109(9):1540-1553.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.03.002. Epub 2021 Mar 18. PMID: 33740417.

Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020; 22(12): 81.

10.1007/s11920-020-01208-6

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11920-020-01208-6